Watch a high-status figure explain a complex crisis—a CEO discussing a market crash, or a pundit diagnosing a political shift. You will rarely hear them stumble. You will not hear “we suspect” or “the evidence is mixed.” Instead, you encounter a flat, impermeable surface of fact. This is what happened. This is what it means.

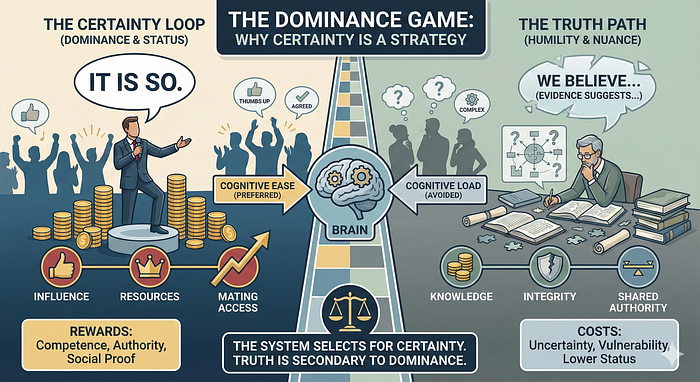

We are conditioned to interpret this unwavering presentation as evidence of competence. We assume the speaker has access to a clearer reality than we do. But if we strip away the content and look only at the behavior, a different pattern emerges. In the competitive hierarchies of business, politics, and academia, asserting certainty is rarely about informational accuracy. It is a strategy for dominance.

From Physical to Narrative Control

The implicit promise of public discourse is that we are all engaged in a collaborative search for truth. The historian explains the past; the scientist describes the physical world. But the “dominance game” operates on a more primal logic. It is not about discovering reality; it is about defining it.

In evolutionary terms, this is a shift from the physical to the narrative. Where our primate ancestors established hierarchy through territorial control and physical aggression, modern humans establish it through “reality-control.” The individual who can successfully set the frame—who can declare, without hesitation, this is how the world is—forces others to operate within that description. To set the parameters of reality is the ultimate power move.

The Cost of Qualification

This explains why high-functioning individuals in these systems so rarely speak in hypotheticals. To say “it might be” is to invite collaboration and debate. To say “it is” is to close the door. It establishes a hierarchy where the speaker is the source of truth and the listener is the recipient. Every qualifier, every “I think” or “perhaps,” is a micro-surrender of status. It signals vulnerability. It admits that the speaker is subject to the same possibility of error as the audience.

For the status-seeking actor, this vulnerability is intolerable. Their communication is not oriented toward an external, objective anchor—a truth that exists independent of them. Instead, the primary reference point is the self. Communication becomes purely utilitarian: What must I say to maintain my position?

In this self-referential loop, truth is only valuable insofar as it supports the speaker’s utility. If a fact is convenient, it is weaponized. If it is ambiguous, it is flattened into certainty. The goal is not to map the territory, but to own it.

Why the Environment Selects for This

The tragedy is that our environment aggressively selects for this behavior. We are, by nature, cognitive misers. Nuance is mentally taxing; it requires us to hold competing possibilities in our heads. Certainty is efficient. It offers the relief of a settled question. We gravitate toward the leader who offers a simple “X causes Y” over the scholar who offers a complex web of probabilities.

Our institutions amplify this flaw. Algorithms favor the boldest claims, pushing high-engagement absolutes over tentative corrections. Corporate and academic structures promote those who can project authority, filtering out the cautious and the self-critical. Even in our personal lives, we often confuse the feeling of conviction with the presence of competence. We reward the person who sounds right, regardless of whether they are right.

This creates a “certainty loop.” The successful actor learns that epistemic humility is a luxury cost they cannot afford. To admit doubt is to lose the room. So they double down, eliminating ambiguity from their performance, not because they are necessarily dishonest, but because they are adapting to a system that punishes hesitation.

Reading the Game

For those paying attention, this reframes the question. Instead of asking “Is this true?” we might ask something stranger: “What is the utility of this certainty?”

We can test this by looking for flexibility. When a speaker is challenged, do they engage with the counter-evidence, or do they deflect and reframe? Do they treat a correction as a helpful data point, or as a threat to their status? If the ego and the claim are fused, any challenge to the fact is experienced as an attack on the self.

Perhaps the prevalence of unearned certainty is not a glitch but an adaptation—the optimized output of a competitive social animal operating in a system that punishes hesitation.

This leaves us in an uncomfortable place. We can recognize the game, but recognizing it does not exempt us from playing. The same pressures that shape the pundit shape the listener. Even now, reading this, some part of you may be waiting for me to offer a confident conclusion—to close the loop, to tell you what it all means. That pull toward resolution is the very thing worth noticing.