When we encounter harm—whether in a work of art that disturbs us or a person whose actions wound us—we face a choice. Do we respond with a label that closes inquiry, or a question that opens understanding?

Consider the phrase “ambitious but flawed.” It sounds objective, a balanced critique. But often, it functions as a gatekeeping mechanism, a way for those in power to dismiss what threatens their hierarchy without having to explain why. Now consider a different phrase, spoken by a resident in a dangerous neighborhood: “He is evil.” This, too, is a label. But its function is entirely different. It is a rapid threat assessment, a necessary heuristic when survival is at stake and deep analysis is a luxury one cannot afford.

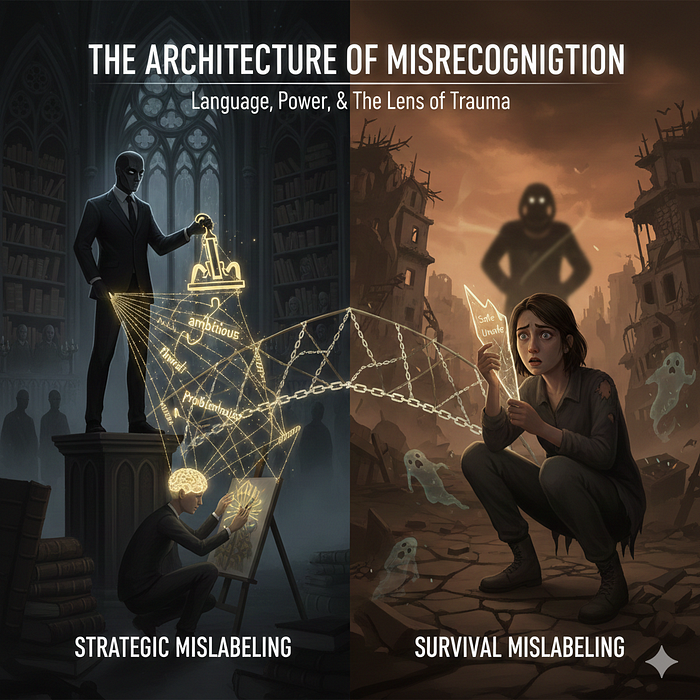

These two instances reveal a paradox: the same linguistic mechanism—vague labeling—serves opposite functions depending on who is speaking. Understanding this distinction is the difference between perpetuating harm and interrupting it.

The Weapon and the Shield

We can map mislabeling into two distinct categories. The first is Strategic Mislabeling, a tool of the secure. In Julius Caesar, Brutus doesn’t kill Caesar for a crime; he kills him for a quality: ambition. Watch how the language works: Caesar’s potential for tyranny is treated as actual tyranny. An abstract trait substitutes for concrete evidence. Brutus had the time, resources, and safety to analyze Caesar’s actual governance, but precision would have undermined his cause. Vague language allowed him to maintain plausible deniability and rally others through abstract fear. Here, the label is a weapon: it enables those in power to harm while believing they are being rational.

The second is Survival Mislabeling, a tool of the vulnerable. Consider a child raised in a violent home who grows up to view all authority figures as “dangerous.” This isn’t a philosophical error; it is a survival code installed by early violation. When a community under siege labels an aggressive member “bad,” they are not engaging in sociological analysis; they are asking, “Will this person hurt me today?” From the outside, we might judge this labeling as unsophisticated. But look at the context: no access to mental health resources, no safety to trace trauma history. The label is a shield: a rapid sorting mechanism deployed when deeper inquiry could be fatal.

The tragedy is that the first type often creates the conditions for the second. Power structures use strategic vagueness to dominate, generating the scarcity and trauma that force the vulnerable to rely on crude, binary labels for protection. The powerful then point to these crude labels as evidence of the vulnerable’s “natural” inferiority, justifying further dominance.

The Mechanics of Trauma

To break this cycle, we must shift our diagnostic question. When someone exhibits harmful behavior, we typically ask: “What kind of person does this?” A more useful question is: “What kind of experience produces this behavior?”

This is not about absolving responsibility; it is about locating causation. Research in trauma studies suggests that extreme or chronic threat fundamentally alters how a person processes reality. The sequence is mechanical: a child experiences betrayal; their nervous system generates protective strategies like hypervigilance or preemptive aggression; these strategies become automatic, operating below conscious awareness. Years later, what society calls “bad character” is often a survival system operating in the absence of the original threat.

If we misdiagnose a trauma response as a moral failing, our interventions will fail. Punishment without understanding simply confirms the subject’s worldview that power equals pain, reinforcing the very behavior we seek to stop. We become part of the cycle we claim to oppose.

Three Levels of Seeing

Interrupting this reproduction of harm requires discernment at three levels.

First is Immediate Containment. When a person is drowning and pulling others under, you do not analyze their swimming technique; you establish distance. This is pragmatic safety. We contain the behavior without necessarily condemning the being. The principle is simple: stop the bleeding, but don’t blame the blood.

Second is Accurate Diagnosis. We must separate observation from conclusion. Instead of “They are violent by nature,” we observe, “This person responds to perceived threats with immediate aggression.” We identify the mechanism—the software running the behavior—so we can address it effectively. In interpersonal conflict, this means shifting from “You are controlling” to “When X happens, you respond with Y, and I experience this as Z.” The first closes the person; the second invites them into shared investigation.

Third is Addressing the Source. We ask what created this pattern. What institutions normalize the original harm? What social conditions make defensive aggression necessary? In art criticism, instead of dismissing a work as “ambitious but flawed,” we might ask, “What does the gap between intention and execution reveal about the constraints the creators worked within?” If we only address symptoms while leaving the generating conditions intact, we guarantee the pattern’s return.

The Privilege of Nuance

We must be honest: applying this kind of analysis is itself a privilege. The critic who dismisses a work as “flawed” has the luxury of nuance but chooses not to use it. Their vagueness is an ethical failure. But for the person in immediate survival mode, the inability to look deeper is a material constraint.

We cannot demand nuanced discernment from those fighting for breath. The framework does not ask the drowning to analyze the water. Instead, it asks those on the shore—those with resources and safety—to stop weaponizing vagueness and start creating conditions where deeper seeing becomes possible for everyone.

The Compound Effect

Even imperfect application matters because consciousness is contagious. One person in a traumatized community who begins to see patterns differently creates a small field of possibility. They might not transform the whole system immediately, but they model that a different response is possible.

One person pauses before reacting. Another notices the pause. Someone else tries pausing once. The community’s reflexes begin to shift—not quickly, not completely, but directionally. Each moment of recognition is a microchip of consciousness entering the system. It doesn’t need to solve everything; it just needs to be slightly different than pure reaction.

Toward Conscious Discernment

The “architecture of misrecognition” persists because it is easier to label than to look. Labels offer the comfort of certainty; looking offers the discomfort of complexity. But only looking—truly seeing beneath the symptom to the structure—offers any possibility of change.

This does not mean we tolerate harm. It means our response to harm becomes surgical rather than reactive. We stop fighting symptoms and start dissolving their source. The highest function of consciousness is not to judge more harshly, but to see more clearly. When we see clearly enough, our responses naturally become more precise—not softer, but more effective.