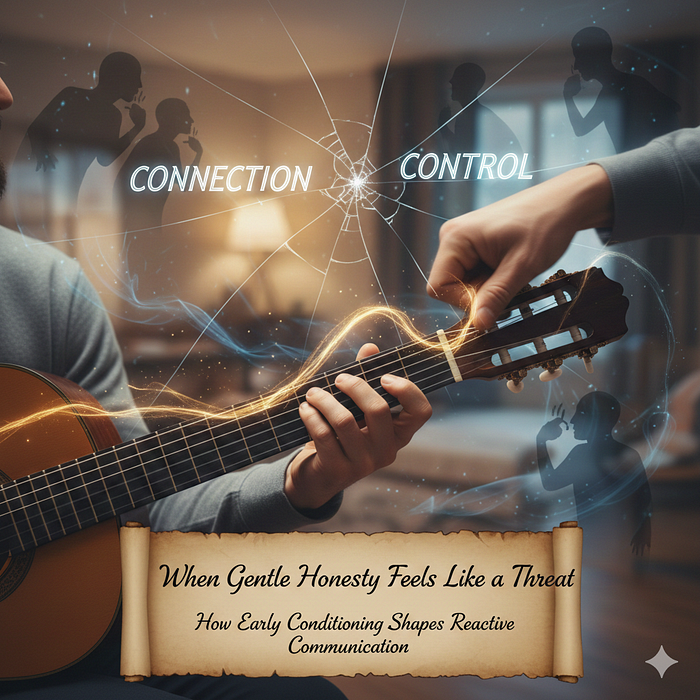

A musician’s D string is slightly flat. You mention it, softly. Instead of making a subtle adjustment, they twist the tuning peg dramatically high—nearly turning it into an E—and look at you as if to say: “Is this what you wanted?”

Now the dynamic has flipped. You’re the one who must explain yourself, defend your intention, reassure them. The original issue gets buried under a power reversal.

This pattern shows up everywhere: a small correction triggers something far bigger than the moment deserves. The reaction isn’t really about the mistake. It’s about what being corrected once meant.

The Equation Written Early

Many people grow up in environments where correction isn’t guidance—it’s dominance. A child habitually “corrected” through teasing, shaming, or competitive one-upmanship learns a dangerous equation: Correction equals hierarchy. Feedback equals control. Self-reflection equals weakness.

Later, even thoughtful, gentle reflection can trigger a defensive spiral. The nervous system isn’t hearing the present person. It’s hearing loud, dangerous echoes of the past.

In this conditioned state, gentleness feels suspicious. Honesty feels dangerous. The present person gets mistaken for the old pattern.

The Brilliance of the Overcorrection

The dramatic twist of the tuning peg is actually a clever defensive move. It lets the person avoid the subtle sting of being wrong, instantly regain control, shift the focus back onto the corrector, and protect a fragile sense of competence.

It’s not that they “can’t take feedback.” They simply never learned what safe feedback feels like.

But this pattern exhausts the person trying to offer it. Being met with defensiveness when you’re genuinely trying to help creates its own wound. Over time, people stop offering feedback altogether—not out of cruelty, but out of self-preservation.

When Both People Are Conditioned

The pattern becomes exponentially more complicated when both people carry this conditioning. Person A offers gentle correction. Person B overcorrects defensively. Person A feels misunderstood and becomes reactive. Person B feels vindicated: “See? You were attacking me.” Both retreat, certain the other is the problem.

In these dynamics, there is no stable person. Both are simultaneously wounded and triggering. This is where relationships get stuck, where the same fight replays with different content but identical structure.

What “Gentle” Feedback Sometimes Hides

Not all “gentle” feedback is actually gentle. Sometimes what feels calm to the giver carries undertones of subtle superiority, impatience, or a need to be right more than a desire to help.

People who’ve been corrected harshly often develop exquisitely sensitive radar for contempt. Sometimes they’re picking up on signals the corrector doesn’t know they’re sending.

This doesn’t excuse defensive overreactions. But it complicates the narrative. Both people may need to do inner work.

The Death by a Thousand Gentle Corrections

There’s another pattern that deserves attention—one that’s insidious precisely because it wears the mask of care.

A single piece of thoughtful feedback is helpful. But when someone consistently offers “gentle” observations about how you tune your instrument, phrase your sentences, organize your workspace, express your emotions, dress, eat, drive—something darker is happening.

Each correction, taken alone, seems reasonable. The person offering it can point to their soft tone, their good intentions. But the cumulative effect is devastating: you begin to lose your sense of agency. You start second-guessing every move, performing for an invisible observer, wondering: “Will this be corrected too?”

The “gentle corrector” often genuinely believes they’re being supportive. They may have no awareness they’re slowly colonizing someone else’s decision-making. Meanwhile, the person being corrected finds themselves in an impossible position: accepting every correction means losing themselves; pushing back risks being labeled “defensive.”

This is boundary erosion disguised as care.

The Critical Distinction

The difference between helpful feedback and subtle control isn’t always in the content—it’s in the pattern. Helpful feedback addresses specific issues, leaves space to disagree, respects autonomy, and stops when acknowledged. Subtle control addresses everything, creates pressure through repetition, persists when the person doesn’t change, and extends into uninvited areas.

The key question isn’t “Is this feedback gentle?” but “Does this feedback respect my agency?”

You can be wrong about something and still have the right to stay wrong. Your autonomy doesn’t require you to be optimal—it requires others to respect your sovereignty over your own choices.

The Only Reliable Cue

There is one reliable cue that can teach the nervous system the difference between genuine reflection and manipulative correction: stable, non-reactive presence.

A manipulator or dominant figure will always escalate. They become offended, cold, superior, or punitive when their correction isn’t immediately accepted.

A truly grounded person does the opposite. They don’t shame, withdraw affection, use the moment as leverage, or take the defensiveness personally. They simply hold the space with quiet clarity.

Over time, this consistency establishes a new equation: Feedback can be safe. Honesty can be supportive. Correction can be collaborative.

The Limits of Presence

Being the stable, non-reactive person requires enormous emotional bandwidth. It means absorbing someone else’s defensive maneuvers without becoming reactive yourself—sometimes for months or years, with no guarantee of transformation.

Not everyone has that capacity. And some people never make the leap to trusting gentle feedback, no matter how consistently safe you are. Their conditioning was too severe, or they’re not ready for that psychological work, or they’ve built their entire identity around never being “the one who’s wrong.”

There’s a difference between growth-oriented relationships where stable presence creates transformation, and stuck ones where you’re just absorbing chaos indefinitely. Knowing which situation you’re in matters.

What Healing Requires

Real transformation isn’t about one person perfecting their calm delivery. It’s about mutual recognition—both people seeing how their histories collide in the present moment, and choosing something different together.

For the person who overcorrects: noticing the gap between your response and the actual threat present. Asking whether you’re reacting to this person or to your history. Learning to tolerate the discomfort of being gently wrong.

For the person offering feedback: examining your own need to correct. Noticing when you feel superior, impatient, or frustrated. Accepting that your impact might not match your intention.

The cycle of reactive communication breaks not when one person becomes perfect at staying calm, but when both stop needing to win. When correction can be offered without superiority and received without collapse. When being wrong becomes information rather than identity.

The nervous system doesn’t need perfect people. It just needs ones who stay present through the mess, who own their part, and who keep choosing connection even when defense feels safer.