Abstract

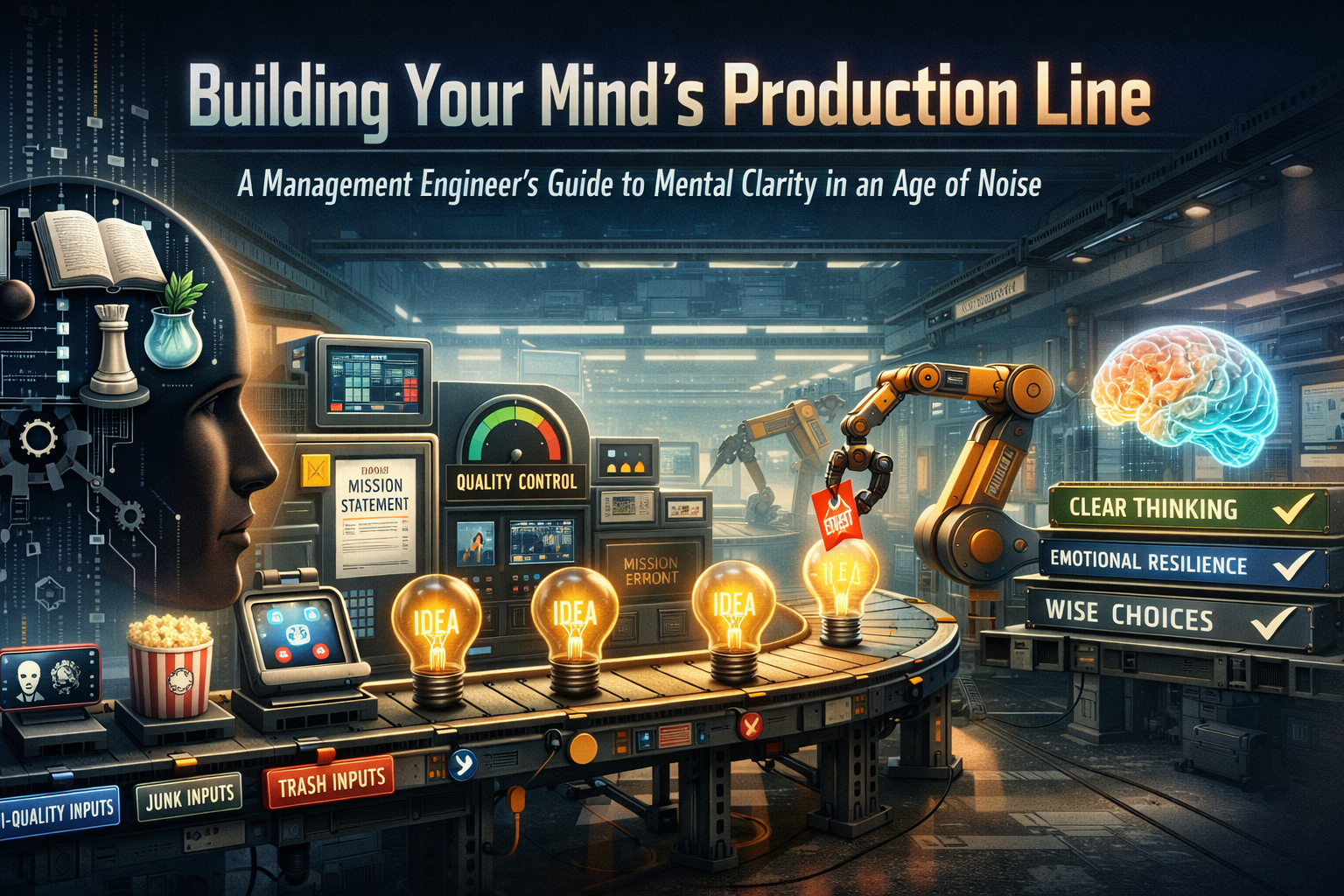

This article proposes a systems-engineering approach to mental life. It treats the mind as a high-stakes production system that transforms informational inputs into beliefs, emotions, and decisions. In an environment where information is cheap and attention is hunted, unregulated cognitive “production lines” are vulnerable to systematic distortion. The paper outlines a four-part framework—input audit, system architecture, continuous improvement, and social interface design—for cultivating cognitive sovereignty: the capacity to maintain clarity and ethical orientation under persistent noise.

1. Introduction

For most of human history, the central epistemic problem was scarcity of information. Access to books, formal education, and expert judgment was limited. In the contemporary media environment, this condition has inverted. Individuals now inhabit an information ecology in which data are abundant, but attention has become the constraining resource.

Within this context, the human mind is frequently treated not as a protected domain of deliberation, but as an externally programmable substrate. Advertising infrastructures, recommendation systems, and political communication strategies are competing attempts to shape the “throughput” of individual cognition in ways that serve institutional objectives. The resulting configuration resembles a production line whose parameters are set by external actors.

If an individual occupies a mind but does not participate in specifying and monitoring its operating conditions, agency is compromised. The person becomes effectively downstream of systems they do not control. Under these conditions, appeals to willpower or generic “self-discipline” are insufficient. A more structural response is required.

The central claim of this article is that principles from management engineering and quality control can be applied to mental life. By articulating design specifications, implementing filtration and evaluation protocols, and engaging in systematic failure analysis, individuals can increase the reliability and ethical quality of their cognitive outputs.

2. Input Audit: Forensics of Influence

Any production system is constrained by the quality and structure of its inputs. You can’t get reliable outputs from consistently degraded raw materials. Analogously, it is difficult to sustain nuanced judgment and emotional stability when a large proportion of one’s informational diet is optimized for novelty, outrage, or tribal reinforcement.

In informal practice, many people operate with effectively open loading docks: any source that can reach a screen or speaker is admitted. An academic treatment benefits from a more explicit input taxonomy and a clearer mission profile.

2.1 Mission Profile

From a systems perspective, the first task is to specify the intended function of the cognitive system. Instead of a vague aspiration to “be informed,” it is more precise to define a mission such as:

The mission of this cognitive system is to support accurate judgments, emotional regulation, and ethically grounded decisions under conditions of uncertainty and time pressure.

Once such a mission profile is articulated, candidates for informational input can be evaluated with respect to whether they are likely to advance or impair that mission.

2.2 Input Taxonomy

Rather than classifying information by topic alone, classify by cognitive nutritional density and by typical effects on attention and affect.

Class A: High-Tensile Raw Materials

- Deep texts and long-form argument: Extended works that require sustained engagement and provide structured models or theories.

- Primary sources: Direct access to data, transcripts, or original research, rather than second-order commentary.

- Direct experience: Engaging in tasks, dialogue, and embodied practice, which provide rich feedback.

- Silence and reflection: Periods without new input, during which consolidation and integration can occur.

Class B: Processed Substitutes

- Summarized news and commentary: Aggregated or curated information that favors brevity and affective charge.

- Infotainment formats: Content that blends information with narrative and aesthetic appeal, often simplifying complexity.

- Opinion on opinion: Layers of commentary that add social positioning without proportionate informational gain.

These are fine in moderation, but should not form the structural core of the cognitive diet.

Class C: Corrosive Inputs

- Algorithmically amplified outrage: Streams selected primarily on the basis of engagement metrics, often privileging conflict and fear.

- Manipulative narratives: Content that primarily seeks behavioral compliance or identity fusion, rather than understanding.

- Global cynicism: Narratives that erode the possibility of trust, meaning, or shared reality.

These inputs degrade the cognitive system over time. They normalize reactivity and narrow the space of conceivable responses.

2.3 Invisible Inputs and Delivery Mechanisms

It is not only the semantic content of information that matters, but also the delivery channel and temporal patterning. A dense book imposes friction; the reader must initiate engagement and sustain attention. By contrast, notifications and auto-play mechanisms operate on a “push” model, repeatedly inserting content without intentional initiation.

These differences constitute distinct input interfaces. High-interruption interfaces fragment processing and reduce the probability of deep integration. Even when the nominal content is sophisticated, consuming it solely through short-form clips trains temporal expectations misaligned with genuine comprehension.

A simple diagnostic procedure is a short-term input audit. Over a defined period (for example, three days), individuals can log sources and approximate durations of all informational exposures, then categorize them using the above taxonomy. If corrosive inputs routinely constitute a substantial fraction of total exposure, the system is operating outside of its design envelope.

3. System Architecture: Defense in Depth

Managing inputs is necessary but not sufficient. Internal processing architecture—the set of implicit and explicit procedures applied to incoming information—determines how that information is transformed.

3.1 The 360-Degree Evaluation Protocol

To avoid purely reactive uptake of salient claims, formalize an evaluation protocol. One such protocol involves four complementary passes:

- Surface description: Articulate the literal claim being made, in neutral language.

- Incentive analysis: Identify plausible material, status, or ideological incentives that might shape the presentation.

- Omission scan: Note variables, perspectives, or counterevidence that appear absent or underrepresented.

- Steel-manning: Construct the strongest reasonable argument against the claim, or for a competing hypothesis.

This procedure does not guarantee correctness, but it systematically increases the dimensionality of evaluation and reduces susceptibility to one-dimensional narratives.

3.2 Reverse Reading and Narrative Inversion

Popular narratives often allocate critical or systemic observations to antagonistic figures while assigning moral legitimacy to defenders of the status quo. Analytically, decouple the accuracy of a diagnosis from the acceptability of the proposed remedy.

For example, in various fictional and non-fictional contexts, actors positioned as “villains” articulate concerns about resource depletion, institutional corruption, or structural inequality. Consider how certain revolutionary figures diagnosed real institutional failures—exploitation, corruption, inequality—even when their proposed remedies proved catastrophic. An academically oriented reader can treat these diagnoses as hypotheses to be examined, rather than as propositions to be rejected solely on the basis of who voiced them.

This practice of narrative inversion fosters dimensional awareness: the ability to entertain multiple partial truths without collapsing into either uncritical endorsement or total rejection.

3.3 Pause Protocols as Cognitive Circuit Breakers

High-voltage affective responses—such as sudden indignation or fear—are not inherently problematic. They become problematic when they directly trigger public action without intervening reflection.

Borrowing from electrical engineering, one can design “circuit breaker” rules. A simple rule is a mandatory delay for high-impact reactions: if a piece of information elicits an immediate urge to post, share, or retaliate, no external action is taken until a specified cooling-off period has elapsed (for example, 24 hours). Most perceived emergencies fade after sleep and additional context.

4. Continuous Improvement: Quality Control for Cognition

Quality management frameworks focus on identifying, measuring, and reducing defects in a process. When applied to cognition, a “defect” can be defined as a recurring pattern of thought or interpretation that systematically leads to error, unnecessary suffering, or impaired functioning.

4.1 Common Cognitive Defect Patterns

Several well-documented cognitive patterns can be conceptualized in these terms:

- Catastrophizing: Extrapolating from a single adverse event to an extreme negative outcome (for example, “I made a mistake” → “I will be fired” → “I will ultimately fail at life”).

- Mind reading: Attributing hidden, typically negative motives to others without adequate evidence.

- Binary sorting: Forcing complex agents or issues into mutually exclusive categories (“ally” versus “enemy”) to reduce processing demands.

Treating these as defects invites systematic monitoring and remediation, rather than moral self-condemnation.

4.2 Failure Analysis Logs

When the cognitive system “crashes”—for example, during disproportionate anger, prolonged rumination, or susceptibility to misleading information—it is possible to perform a simplified root cause analysis. A typical sequence might include:

- Event description: A concise account of what occurred.

- Immediate precipitant: The proximal trigger (for instance, a specific interaction or piece of news).

- Upstream conditions: Prior states such as fatigue, accumulated exposure to corrosive inputs, or unmet physiological needs.

- Process adjustment: A concrete change to input patterns or internal procedures (for example, temporal boundaries on news consumption).

The point is learning and system refinement, not assigning moral fault.

4.3 Maintenance Schedules

High-utilization systems require scheduled maintenance to avoid cumulative degradation. Analogous practices in cognitive life include:

- Daily intervals of input-free time: Periods without digital or informational stimuli, allowing for consolidation and spontaneous association.

- Regular digital sabbaths: Extended intervals (for example, 24 hours) without networked devices, which can recalibrate reward sensitivity and attentional rhythms.

- Periodic deep-work engagements: Multi-hour or multi-day immersion in a single domain, supporting the reconstruction of longer attention spans.

These are operational requirements for sustaining reliable performance in high-noise environments, not ascetic ideals.

5. Social Interface: Managing Cognitive Environments

No cognitive system operates in isolation. Human agents are embedded in social networks that can either stabilize or destabilize their internal processes. The design of interpersonal “interfaces” is a critical component of cognitive engineering.

5.1 Interface Rather Than Merger

Software systems often employ application programming interfaces (APIs) to enable interaction without full integration. A similar principle applies to emotional and informational exchange. You can recognize and respond to another’s distress without adopting their interpretive frame or affective state as your own.

This stance preserves empathy while maintaining system boundaries. In practical terms, it may involve explicit internal distinctions such as “I can acknowledge this person’s anger without concluding that their evaluative judgments are accurate.”

5.2 Rate Limiting and Boundary Conditions

Some relationships and platforms function as high-volume sources of corrosive input. This invites rate limiting: constraining the frequency or duration of exposure. This can range from simple notification settings and time windows for engagement to more substantive renegotiation of conversational norms.

The objective is not social withdrawal, but alignment of social exposure with the mission profile defined earlier.

5.3 De-escalation of Conflict Loops

Certain interaction patterns resemble feedback loops that escalate conflict. One behavioral strategy for interrupting such loops is to adopt a low-reactivity stance sometimes called “grey rocking”: responding neutrally and boringly to deny the other party emotional fuel. This strategy can prevent external attempts at manipulation from hijacking internal processing capacity.

6. Conclusion: Cognitive Sovereignty as Relational Capacity

Treating mental life through the lens of production systems and quality control risks sounding mechanistic. The intent is not to reduce persons to machines, but to borrow analytical tools that clarify how attention, interpretation, and decision-making are shaped.

Without some form of explicit design and monitoring, the contemporary attention economy will, by default, allocate significant portions of individual cognitive bandwidth to external agendas. The framework sketched here—input auditing, architectural protocols, continuous improvement, and social interface design—offers one way to reclaim a degree of control.

Importantly, cognitive sovereignty is not merely a private good. A mind less captured by reactive loops and manipulative narratives can participate in shared inquiry, listen without projection, and sustain ethical commitments under pressure. Managing your own cognitive production line is a form of service: it increases the reliability with which you can offer clear attention and grounded judgment to others.

The ultimate “product” of such a system is not perfection, but increased capacity—for understanding, for responsible action, and for relationship. Designing and maintaining that system is an ongoing, unfinished task, but one that becomes more tractable when approached with the tools of engineering as well as the depth of human experience.